Human to Human: Responding to distressed students with care, compassion, flexibility and expectations

“A common reaction when faced with student struggle is to want to refer the student to a mental health provider. However, supporting a student’s well-being does not always involve a clinical solution as much as a relational one. By shifting away from clinical language (e.g., depression, anxiety) to describe common student struggles (e.g., loneliness, fear of failure), we are in a better position to relate to them in a supportive, engaging manner and help them feel that they belong here. For many students, a connection with a trusted adult will be all the healing they need.”

Emory, 2022

This does not diminish the fact that many students are struggling with complex mental health challenges and need professional support. In those cases, you are an important conduit to campus resources and supports (mental health, academic, wellness, etc.) that students can access, but may not be aware of or feel able to navigate.

Why are instructors an important part of the system in caring for students?

Instructors are often uniquely positioned to notice changes in students that are concerning. Sometimes those changes occur in an individual student, in a subset of students, or more broadly across the student population. When troubling events happen on campus or in the broader landscape, the classroom may be the only place students are expected to show up. This places instructors in a distinct position to offer students care and support. You are not your students’ therapist, but you can offer connection, compassionate curiosity, timely response, and a balance of care and expectation.

When noticing worrisome changes in their students or sensing that they may be struggling, there is at times a tendency on the part of faculty to: become anxious about addressing these concerns directly; believe that students’ emotional lives are separate from their academic work; or assume someone else will pick up on it, all of which can lead to inaction. The underlying causes of the student’s symptoms you might see can be complex and are unknowable to you. It is important not to make assumptions, to minimize, or to judge – just to respond to the concerns you are noticing proactively and compassionately.

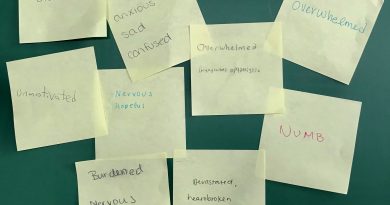

What might students in distress be experiencing that affects their academic work?

Past experiences, positive and negative, inside and outside the classroom can affect students’ ability to engage and be academically successful. Current events on and off campus may also be a contributing factor. Student identities are also at play. Continuous marginalization and oppression related to race, gender, sexual orientation, and in some cases, socio-economic status and other social identities, compound distress and possible trauma.

As you consider how to respond to and support your students, it is helpful to be aware that they may be living with very real and persistent physiological pain (neck pain, headaches, insomnia or sleeping more than usual, fatigue) as well as psychological symptoms that compete with their ability to focus and complete their work. Students may experience difficulty focusing (on content, lectures, readings), retaining and recalling information, maintaining consistent and timely attendance, reduced emotional regulation, a fear of taking risks, debilitating anxiety about deadlines and exams, aversion to group work, feelings of helplessness, and social withdrawal and isolation. Late arrival consistently to class, absences, late or missed work, decreased quality or completion of work, and non-responsiveness might be symptoms of distress that you will notice as the instructor.

What is a compassionate and flexible response?

Mays Imad, educator and neuroscientist, conveys that dealing with students struggling with mental health or emotional issues “…does not require that the educator has training in social work or clinical psychology. We are not diagnosing or treating our students…and it does not mean that there are no rules, and students can ‘get away’ with anything” (Imad, 2022, p. 39). Knowing what students may be experiencing will hopefully help you offer a compassionate and measured response to those who may need additional flexibility in completing the course requirements successfully. This can be complicated to work through, and there are many alternatives.

You may have built some flexibility into your course already through your attendance policies, the ability to skip or drop one or two assignments or grades, and/or the opportunity to make up an assignment or to earn extra points through re-submitting work. Perhaps you have a policy of reaching out to students whose early grades indicate signs of struggle (perhaps nothing to do with mental health), or have created an opportunity to connect early in the semester in your office hours to build connections, or have built in opportunities for social connection through activities in your class. These elements can be helpful for all students, and even more so for students struggling or in distress.

There may be other opportunities for you to offer support as well. If a student’s anxiety around a particular assessment is debilitating – can you offer a different form of that assessment? An extension? What is important to know is that the learning is sufficiently assessed, and that equal is not always equitable. And for some students, all of the support described above may not be enough for them to stay on or get back on track.

A Few Things to Keep in Mind

- Make a connection. What you are seeing might be something temporary or very complex, and you may not be able to easily discern, but in either case, establishing connection is important. It is almost always a good choice to check in gently with the student as soon as you notice they may be in distress or struggling. Convey that you are concerned, and that you care about their well being. You might ask “Is there anything that is making it hard for you to be in this class or complete the work?” “How can I support you?” “What kind of support do you have or need?” Notice the use of open, invitational questions that do not suggest the problem or solution.

- Guide the student toward available mental health resources. If you are still concerned after the conversation or in the following classes, you can either refer the student to mental health services or call mental health services for a consultation about what you might do. Make sure you know where to find these resources easily. In the case where you are concerned for a student’s immediate safety, be familiar with and follow your school’s guidelines and do not leave the student alone.

- Guide the student toward academic support. If a student’s work and academic progress are affected, refer them to the Dean of Student Affairs office (or appropriate office at your school), and if an undergraduate, the student’s advising dean. Taking this step early will provide the student expert guidance to develop the broadest set of options available to help them recover, or at least help them make choices that have the fewest consequences.

- Reach out to the Dean of Student Affairs office with your concerns. Remember that you only have one view of the problem and you may not know what consequences are at stake, or whether there is a larger pattern compounding the student’s distress and limiting your ability to offer appropriate or adequate academic support. If other faculty have conveyed similar concerns, this office may have a broader picture of the student’s overall situation and be able to intervene and support you and your student.

- Building flexibility into your courses for those times when students need it, developing positive connections among and with your students, and reaching out when you are concerned are all part of a compassionate approach to teaching.

See Also

- Mental health challenges require urgent response (Inside Higher Ed)

- 4 ways faculty can be allies for college student mental health (ACUE)

- Psychological First Aid: Resources for Faculty in Higher Education (Teaching@Tufts)

References

- “Supporting Undergraduate Students | Emory University | Atlanta GA.” Accessed September 26, 2022. http://campuslife.emory.edu/support/the-blue-folder/undergrad.html.

- Hoch, A., Stewart, D., Webb, K., & Wyandt-Hiebert, M. A. (2015, May). Trauma-informed care on a college campus. Presentation at the annual meeting of the American College Health Association, Orlando, FL.

- Imad, M. (2022). Our brains, emotions, and learning: Eight principles of trauma informed teaching. In Thompson, P., & Cariello, J. (Eds.) (2022). Trauma-informed pedagogies: A guide for responding to crisis and inequality in higher education (pp. 35-48). London: Palgrave/Macmillan.

- Thompson, P., & Cariello, J. (Eds.) (2022). Trauma-informed pedagogies: A guide for responding to crisis and inequality in higher education. London: Palgrave/Macmillan.

- Thompson, P, and Marsh, H. (2022). Centering equity: Trauma-informed principles and Feminist practice. In Thompson, P., & Cariello, J. (Eds.) (2022). Trauma informed pedagogies: A guide for responding to crisis and inequality in higher education (pp. 15-34). London: Palgrave/Macmillan.

Image credit: Alonso Nichols/Tufts University