Innovation and the Future of Work in the Social Sector – A Glimpse into one Recent Graduate’s Research

By Adam Basciano, GBA ’22

Adam Basciano is a graduate from the Fletcher School’s Master of Global Business Administration program. He works in global business advisory and is based in Washington, DC. He is the co-founder and former director of IPF Atid, an international network of Middle East peacebuilders.

Fletcher’s new Global Business Administration program found me at an interesting moment. Working in the social sector at the time, I had been exploring creative ways to disrupt and advance peace amidst the perplexing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Through building up new human infrastructure and working alongside hundreds of organizations across the globe, we had found success in various areas and learned what key challenges exist for small-medium sized nonprofits trying to innovate. Seeing how best practices from the worlds of entrepreneurship and business were not being fully maximized in civil society, I was intrigued by how innovation could be applied at scale to solve big problems.

This gap only became more evident, and pertinent, as social, political, technological, and other realities seemed to be worsening in the United States (and exacerbated by the pandemic). While unique and tied to our own history in various ways, these American challenges also share many similarities with most other democracies and societies across the globe.

How, if at all, could innovation be harnessed to solve the intractable, “wicked” problems that government and business are not well-positioned to address? Could we expand our horizons of what is possible for civil society to achieve? What trends and disruptions will ultimately define the 21st century, and could they be leveraged for the global good? What can history teach us?

This thinking led to a final capstone project that tied these questions together. After a five-month listening tour and over fifty interviews held over Zoom, my Fletcher thesis was complete. Motivated by systems-wide structures and processes (as opposed to individual issues like climate change or poverty), my research focused its scope on areas I knew best: American civil society, social innovation, and the unlimited power of human talent and resources.

“As with most other industries and contexts, the coronavirus pandemic has revealed longstanding shortcomings and disparities across philanthropy and the social sector, signaling areas for growth and expediting trends that were lingering beneath the surface. For social entrepreneurs and civil society organizations, this is a welcomed opportunity.” – from “The Future of Work in the Social Sector: How the Sector Can Harness Next Generation Human Capital and Innovation to Radically Expand Its Capacity.”

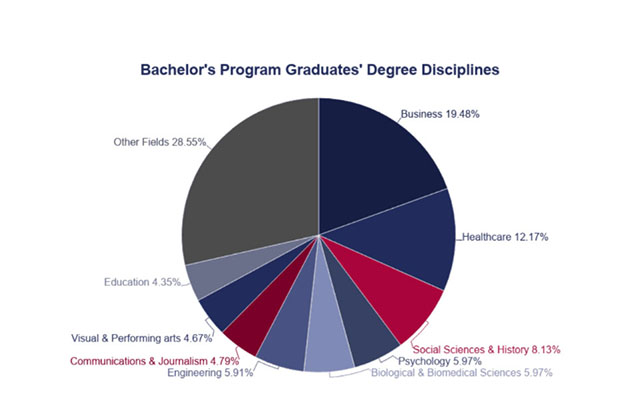

In my “The Future of Work in the Social Sector” report, which can be accessed and downloaded here, I argue that harnessing next generation human capital and institutionalizing innovation represent key strategic priorities for the social sector—and the overall health of the country and planet. Young people today, known by some as “Generation Impact,” are increasingly purpose-driven, entrepreneurial, and ready to address global challenges in their careers. As future decision-makers and stewards, they are also in line to inherit the largest wealth transfer (nearly $60 trillion) in human history. It is therefore critical for the sector (and its partners) to reflect on what is holding it back and begin repositioning to scale its capacity, talent, and leadership in driving impact.

This might mean institutionalizing innovation by normalizing trends like the no-strings-attached approach of MacKenzie Scott and other visionary funders. By providing greater flexibility and agility (by forgoing project-specific grants), organizations are able to better advance creative, innovative solutions for the communities they serve.

Or collectively, we can find a better label than the “nonprofit” tag, because an “industry that works tirelessly to alleviate suffering…and protect our planet deserves a name that honors its aspirations and achievements.” Reframing something as simple as this can go a long way over time in shifting perceptions of how society values the social sector. Advancing other approaches in marketing, such as aligning around a social entrepreneurship positioning (and downplaying appeals to “service” in certain circumstances), can expand and strengthen the talent pipelines of motivated professionals who might consider the sector in their careers.

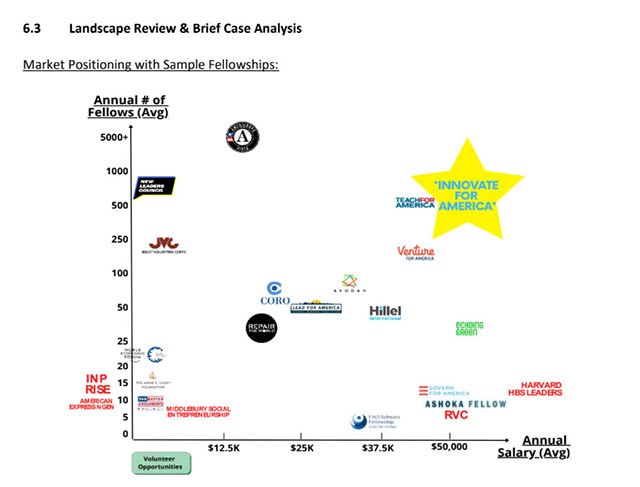

Looking ahead, there are countless other trends and opportunities converging from within, and beyond, the sector that social change agents and their institutions can seize. If we look at how far the social sector has gone in bringing along business and governmental forces to address key challenges of our time, we can only imagine how much more it can accomplish once it internalizes these positive trends across its infrastructure. In my report’s final section, I outline one such hypothetical start-up that brings many of these concepts to life.

Finally, it’s helpful to remember that both civil society and entrepreneurship have always been ingrained within the American DNA. In the beginning of the 19th century, French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville wrote about the central role of American citizen associations (civil society) in his early observations of the American democratic experiment. And with innovation, we may first think about fancy technologies and images of Steve Jobs, but the truth is that some of the country’s greatest innovators were operating from civil society. A recent book, for example, rightfully argues that figures like Harriet Tubman count among the country’s greatest entrepreneurial pioneers for their relentless out-of-the-box thinking and disruptive leadership.

As trust in institutions diminish and social compacts remain in flux, according to Deloitte’s Monitor Institute, democracies and their structures of power face no shortage of challenges. For them to succeed in the 21st century, they must not only be defensive against threats — but on the offensive and visionary. Civil society perhaps represents our best target for investment.