The Power of Collaboration

Tufts CEEO and LEGO Foundation are doing grant projects differently. Here’s how their collaborative approach is transforming educational outcomes.

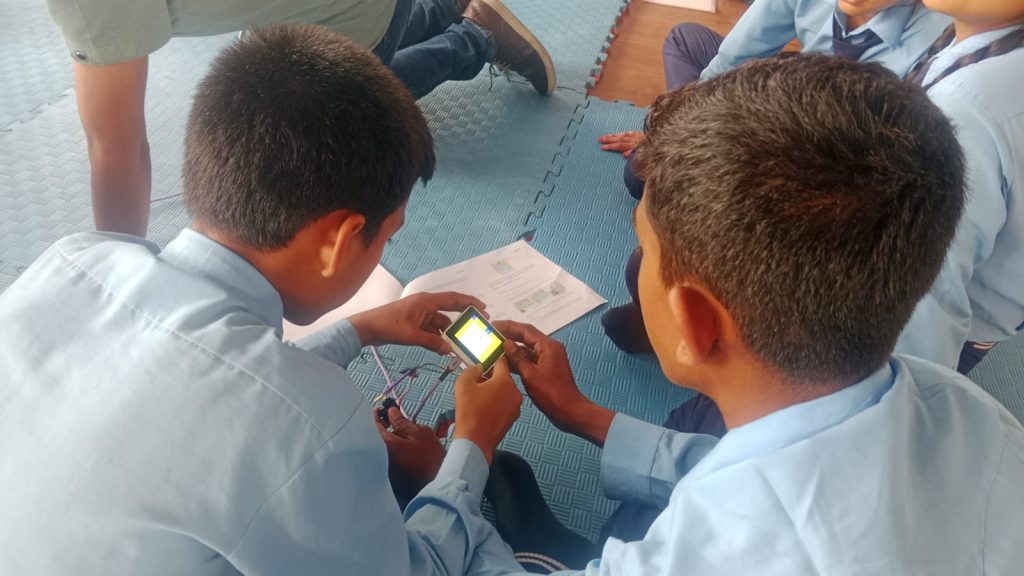

Imagine: a classroom of desks in orderly rows, teacher up front, delivering a lecture. Some students take notes and perhaps nod along, but others doodle, daydream, or appear distracted. This behavior is common in classrooms everywhere, said Hasin Shakya, the director of Karkhana Samuha, a Nepali non-profit whose mission is to advance innovation in education among marginalized communities in Nepal. His organization augments Nepal’s national STEM curricula by providing schools with PEBL Toolkits that empower teachers to bring hands-on, play-based learning into their classrooms because, he said, “students learn best when they are creating, when they are using their hands, when they are playing.”

In 2021, Karkhana was one of eight geographically diverse community-based educational institutions to benefit from a grant from the LEGO Foundation, whose aim was to support playful engineering-based learning, or PEBL. The $2.8 million grant was administered by Tufts University’s Center for Engineering Education and Outreach (CEEO).

Why Playful Learning?

Studies show that by creating experiences that are joyful, meaningful, actively engaging, iterative, and socially interactive, play-based learning promotes healthy child development. Playful learning also enables students to acquire academic content more deeply as well as to develop executive function and social-emotional skills, say researchers at the LEGO Foundation.

But there are real challenges in implementing a playful learning pedagogy. “Schools and teachers are really constrained in what they have the time and resources to implement,” said Merredith Portsmore, director of Tufts CEEO. “Implementing playful approaches is far down the list after required curricula and mandated testing,” she said.

To overcome these challenges and maximize the effectiveness of the grant, Tufts and LEGO created a PEBL Community of Practice (CoP) designed to provide a comprehensive network of support that strengthened the work of each organization.

Each organization was asked to name someone to the role of PEBL fellow, who would be responsible for representing the organization in the CoP. PEBL fellows gathered monthly to share updates, exchange ideas, and provide feedback to each other. They also participated in professional development training in play-based pedagogies led by Tufts educators and educational professionals. Tufts also hired a team of consultants with expertise in makerspace development, educational technology, curriculum design, and teacher training to address individual organizations’ specific areas of need. “The CoP brought together organizations that knew what their communities needed as well as how to navigate schools and systems, and we all came together to learn and share resources,” said Portsmore.

Marketing and graphic design don’t always make it into the budgets of educational non-profits, so Tufts added consultants and staff with writing and design expertise to the CoP. These skilled professionals worked with PEBL fellows and their organizations to create user-friendly educational materials as well as promotional pieces, such as press releases and blog posts, to raise awareness and amplify their success stories.

“This wasn’t your traditional way of handing out funding and coming back at the end to see what had happened. The organizations were really supported and connected throughout the grant-funded project term,” said Sherry Preiss, an educational consultant hired by Tufts, who worked with Portsmore and her team to plan and orchestrate monthly CoP meetings.

As weeks and months passed, Portsmore noticed something else happening. “Organically, organizations started collaborating on their own, bringing their unique knowledge and expertise to help other groups make their work even more impactful,” she said.

We asked the collaborating organizations about the experiences of being part of a Community of Practice of like-minded organizations working toward the same goal. Here’s what they had to say:

White Mountain Science (WMSI)

Littleton, New Hampshire

“One of the most effective things we learned from these monthly collaborations was how to use the LEGO Foundation’s Learning Through Play Rubric,” said Amanda Carron, associate director of programs for WMSI, an organization in northern New Hampshire that offers playful year-round programming for grades K-12 in-school, after school, and through summer camps. The rubric helps teachers determine where students are in the learning process. Fellows watched videos of teachers facilitating PEBL activities and then were asked to identify, for example, whether a student was passively following instructions or actively developing their understanding of the content. Fellows were then asked to consider what pedagogical moves they might make to advance learning outcomes. “The rubric helped us not only establish a common language to talk about playful learning, but also gave us a tool with which we could examine our own teaching practices,” she said.

“The [LEGO Foundation’s Learning Through Play Rubric] helped us not only establish a common language… but also gave us a tool with which we could examine our own teaching practices.

Amanda Carron, WMSI

As a long-running organization, WMSI found itself acting as a mentor to younger organizations in the CoP. For example, Carron was asked to give a presentation on how WMSI created its Mobile STEM Labs, which are vans outfitted with STEM materials so they can reach students in distant locations. Carron worked with a graphic designer from Tufts CEEO to create an easy-to-use guide for any organization interested in Creating a Mobile STEM Lab.

WMSI also mentored KARMA, a relatively new organization located in Navajo Nation, which sought guidance on organizational design and development. Since then, WMSI has captured its best practices in the guide, “Operating a STEM education non-profit.” Meanwhile, KARMA’s PEBL fellow, Keanu Jones, an award-winning filmmaker, shared his storytelling expertise to create a short film about WMSI the organization features on its website to raise awareness among families, educators, and funders.

Maryville University’s Center for Access and Achievement

St. Louis, Missouri

“A lot of what we talked about at our monthly CoP meetings was making our lessons culturally relevant and responsive to the needs of the community,” said Karen Engelkenjohn of Maryville University’s Center for Access and Achievement (CA2), which partners with schools and nonprofits to provide access to high-quality STEM programs.

“St. Louis is going to be home to the National Geospatial Center in a couple of years, bringing thousands of new jobs to our area,” said Engelkenjohn, referring to the $1.7 billion headquarters the US federal agency is set to open in north St. Louis in 2025. “We’re working to reinforce students’ mapping and other STEM skills and prepare students for these exciting career opportunities,” she said.

Engelkenjohn had an idea for how to do that. “Every kindergarten room has a colorful rug with streets and houses,” she said, and wanted to create something similar to help children build a conceptual understanding of the coordinate mapping system. Engelkenjohn sketched out the designs of a playground, beach, and roadway–complete with a grid, coordinates, and a compass rose–and gave them to a Tufts engineering student, who turned them into large-scale, colorful, kid-friendly mats that could be used with LEGO Education DUPLO sets. Imagining all the different ways the MAP MATS could be used in the classroom came easy to Engelkenjohn, who is an educator with over 22 years’ experience in project-based learning. While she is comfortable using LEGO products as learning tools in the classroom, she wanted to make these learning tools accessible to novice teachers, too.

Sherry translated my broad-brush thinking into usable, accessible lesson plans that other teachers could pick up and use.

Karen Engelkenjohn, Maryville University CA2

So, Tufts connected Engelkenjohn with Sherry Preiss, who has a background in publishing, curriculum development, and professional learning. Together, they developed an activity book with 25 teacher-guided playful learning activities, which help students develop spatial recognition skills, numeracy, and letter recognition, as well as an understanding of coordinate grids and maps. “Sherry translated my broad-brush thinking into usable, accessible lesson plans that other teachers, no matter what level of experience they had, could pick up and use.” In addition, Tufts provided graphic designers to amp up the look of the mat and teacher guide.

Use of the mats has been incredible, said Engelkenjohn. “Children instantly respond to the MAP MATS with their imaginations and drive to create,” she explained. She estimates that so far 1,000 students have engaged with the mat activities and that implementation of the project has been able to address some of the equity issues in the St. Louis area.

Ke’yah Advanced Rural Manufacturing Alliance (KARMA)

Navajo Nation

For a young organization like KARMA, one of the benefits of collaboration was the ability to tap into Tufts’ expertise for curriculum development, said Keanu Jones, the PEBL fellow at KARMA, whose organization offers hands-on K-12 programming by partnering with schools in indigenous communities on Navajo Nation and Hopi lands.

“We’re really interested in creating curricula that are culturally responsive and relevant within our communities,” he added. So, when a teacher KARMA works with, Tom Tomas, wanted to bring LEGO robotics into his classroom, Tufts CEEO project administrator, Alison Earnhart, worked with him to co-develop learning activities. This was during the pandemic, so Earnhart worked with students remotely over Zoom, guiding them through robotics engineering and coding challenges using LEGO Education SPIKE Prime Sets while Tufts teaching assistants facilitated virtual breakout rooms with small groups of students. In 2022, Earnhart and a colleague were able to visit students in person as well as lead professional development training with teachers.

Other professional development support from Tufts came via a graduate student who demonstrated how SPIKE PRIME robots could be programmed to speak Navajo and draw patterns on paper that mimic traditional Navajo rug designs or that draw maps used for water hauling.

But professional development training is not enough, according to Denise Masayesva, a veteran teacher and member of the Hopi Tribe, who KARMA hired to offer ongoing support of teachers as they bring play-based STEM activities to their classrooms. “It could be the best, well-funded curriculum complete with resources, but if your teachers are not comfortable, if they don’t feel it’s accessible, it’s just going to sit on the shelf,” she said.

One way to do that, she said, is to look for inspiration in everyday technologies that Hopi communities identify with, such as the bread oven. “Who doesn’t have great memories of the smell of baking bread,” she said. “There’s a lot of cultural knowledge involved in building an oven–like understanding the geology of the sandstone used–which can be an entry point to teach engineering, science, and math,” she said. To empower teachers to mine these rich connections as STEM learning opportunities, Masayesva has led professional development training on PEBL teaching practices and facilitated site visits among Hopi and Navajo schools, so teachers could observe play-based learning in action in the classroom.

It could be the best, well-funded curriculum complete with resources, but if your teachers are not comfortable, if they don’t feel it’s accessible, it’s just going to sit on the shelf.

Denise Masayesva, KARMA

Teach for Nepal

Kathmandu, Nepal

Introducing hands-on play-based activities is a challenge in schools where the traditional, lecture-heavy model predominates and students are expected to move at the pace of the teacher, said Roshan Bhatta of Teach for Nepal (TfN). His organization recruits new college grads to spend two years teaching in schools in the rural part of Nepal. “There’s a tendency among teachers to want to throw materials at students and just get the project done,” saidBhatta. To resist this tendency, he spent a lot of time with his new recruits training them on a play-based pedagogy. “Without the regular CoP meetings, it would be easy to lose sight of the goal, and focus on the product, not the process. But ultimately, learning happens during the process,” he said.

Ultimately learning happens during the process.

Roshan Bhatta

To help them design makerspace learning activities for their classrooms, Bhatta and his cohort of teaching fellows worked remotely with educational consultant John Heffernan, an electrical engineer turned educator, who has taught in K-12 and college classrooms, as well as with a Tufts engineering student. Tufts students also created instructional videos and designed placemats with hands-on engineering challenges that teachers could print and use in their classrooms. Providing onsite support, a Tufts graduate student returned home to Nepal for a summer to work directly with Bhatta and his fellows.

In addition, Bhatta and a group of teaching fellows met weekly online with Sherry Preiss. Together, they created and evaluated lesson plans, analyzed classroom videos, and shared ideas on ways to enrich classroom practice and student learning. They also used Tufts CEEO materials and received guidance from Portsmore on questioning and discussion strategies they could use in the classroom. “By asking students to explain their reasoning with open-ended questions, educators can transform a teacher-led environment into student-centered experience,” said Preiss.

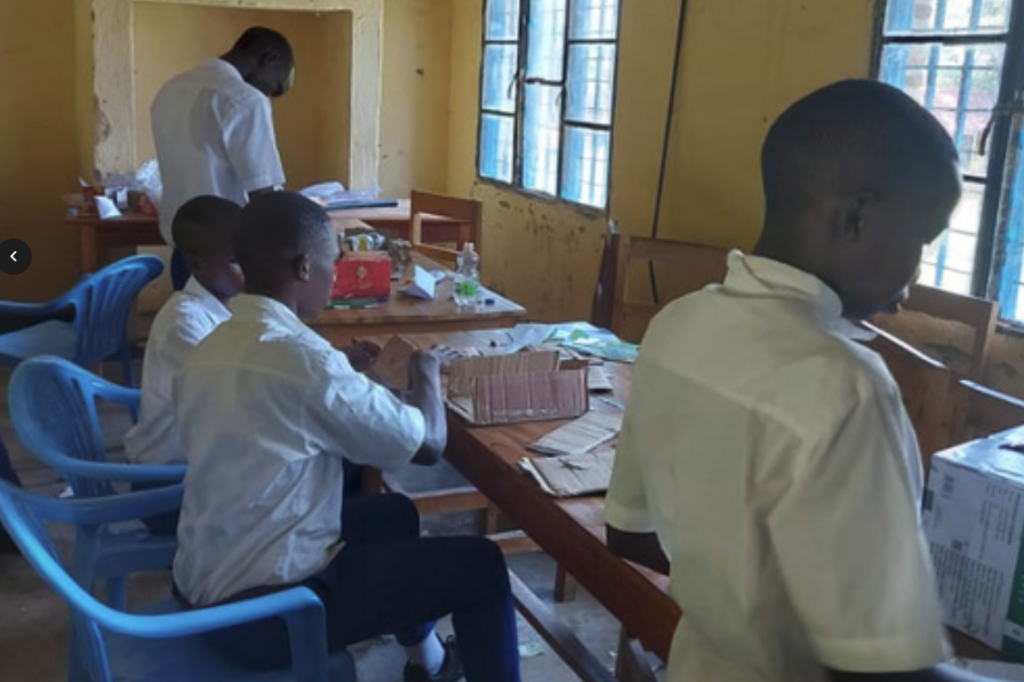

Rwanda Makerspace Consortium

Rwanda

One of the most valuable parts of the PEBL program was the collaboration with Tufts CEEO, said Djamila Khamisi, an engineer and PEBL project manager for the Rwanda Makerspace Consortium. Khamisi’s goal for her PEBL project was to provide training and materials to establish makerspaces in Rwandan schools. In the fall of 2022, Khamisi came to Boston and spent three weeks at Tufts University attending courses, meeting with faculty, visiting area schools, and planning the training program she would lead back home in Rwanda.

CEEO staff Elissa Milto and Alison Earnhart worked closely with Khamis to create materials suitable for primary and secondary school educators, leveraging CEEO’s Novel Engineering activities to introduce engineering through storytelling as well as using Arduino, coding, and electronics to perform everyday problem-solving tasks.

In December that year, Khamisi trained 40 teachers who gathered at the Maranyundo Girls School in the Bugesera district of Rwanda. The teachers came from 21 private and public schools to receive the training. Since then, teachers have set up 20 makerspaces at their schools with materials funded by the LEGO grant.

Inspired by the success of the makerspace competitions hosted by Teach for Nepal, Khamisi organized the consortium’s first maker competition in the summer of 2023. Tufts sent Rwandan undergraduate student interns to the Maranyundo school to assist Khamisi. The interns mentored students as they worked on their projects and created training videos that show students how to use Arduino circuit boards to operate traffic lights, run self-opening doors, and test humidity levels and temperature.

Being able to provide ongoing teacher training is essential in order to continue this work, said Khamisi, who would like to build a digital platform, similar to Karkhana Samuha’s PEBL Toolkit, where teachers can share makerspace activities and lesson plans. “At the end of the day, we want both teachers and students to become problem solvers in their communities,” she said.

At the end of the day, we want both teachers and students to become problem solvers in their communities.

Djamila Khamisi, Rwanda Makerspace Consortium

Karkhana Samuha

Kathmandu, Nepal

“We were constantly getting new ideas from the collaboration,” said Sameer Prasai, Karkhana Samuha’s PEBL fellow. Karkhana Samuha is a non-profit organization in Nepal that provides STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, and math) toolkits to young people through schools and families. As a recipient of the LEGO Foundation grant and part of the PEBL CoP, the organization has rolled out 1,500 PEBL kits and lessons to 3,000 students over a three-phased, 18-month timeline, both in-person and through its website. “Some of the questioning strategies we learned in our sessions with Merredith ended up in our educational guides,” said Prasai.

Karkhana also works directly with teachers through its community of practice, called the Teaching Community of Play, or TeaCoP. Teachers meet weekly to share and explore different play-based teaching and learning approaches. In October 2022, TeaCoP held its first conference for educators interested in implementing playful and engineering-based learning. Keynote addresses were given by Portsmore as well as by Tufts CEEO founder Chris Rogers and LEGO Foundation design specialist Ole Kjær Thomasen.

To be able to change the attitude of the teacher toward this student in that way from ‘this kid cannot learn’ to ‘my methodology was not correct for this kid,’ that is something we are quite proud of.

Sameer Prasai, Karkhana Samuha

What Prasai is most proud of is the effect that the PEBL project has had on the teachers he works with. Many of them are new to teaching and came to the role with preconceived notions of what learning looks like, he said. But since the start of the PEBL project, Prasai has trained more than 50 educators in play-based teaching methodologies. “Teachers keep telling us that students whom they thought weren’t good students–who don’t score high marks on exams, who don’t do their homework regularly, who have disruptive behavior–these are the ones who have benefited a lot” because for the first time teachers have had an opportunity to see their creativity, he said. “To be able to change the attitude of the teacher toward this student in that way from ‘this kid cannot learn’ to ‘my methodology was not correct for this kid,’ that is something we are quite proud of,” he said.