BattleBots and Giant Watermelons: What Playful Learning Looks Like at WMSI Summer Camps

When WMSI program instructor Erin Glocke walked into the classroom at a regional high school in northern New Hampshire, she had a plan. The group of five middle schoolers would spend the week-long summer camp designing and coding robots that could maneuver through mazes. But the kids had a different idea; they wanted to create robots that could battle in an arena like the BattleBots they’d seen on television. And they were really excited about doing it.

By the second day, Erin scrapped her maze plan. BattleBots were on.

Using LEGO Education SPIKE Prime sets, students created robots with scoops, wheels, articulating arms, even a trailer bed designed to push, grab, and flip over opponents. One camper created a robot with a huge drill on the front by stacking a series of gears onto a rod. Another aimed to make his the “chunkiest, hardest-to-flip bot by adding over 28 wheels to his design,” said Erin. “It was awesome. They were all really into it, and they all took different approaches about how they wanted to succeed.”

At WMSI, we’re all about student-driven learning. When there’s an opportunity to follow students’ interests, we take it.

Erin Glocke, Program Instructor at WMSI

WMSI, or White Mountain Science, Inc., runs camps and after school programs throughout northern New Hampshire designed to get kids excited about STEM through a play-based, student-centered approach.

When students are engaged in purposeful play, the students are working hard to accomplish their goal and the learning happens naturally, according to Erin. Because they need coding or engineering to achieve something they are really interested in, they dig into the ideas and tools, she said. More importantly, she added, when you are learning through a playful project, you invoke a host of other skills, such as planning, interaction, and resilience.

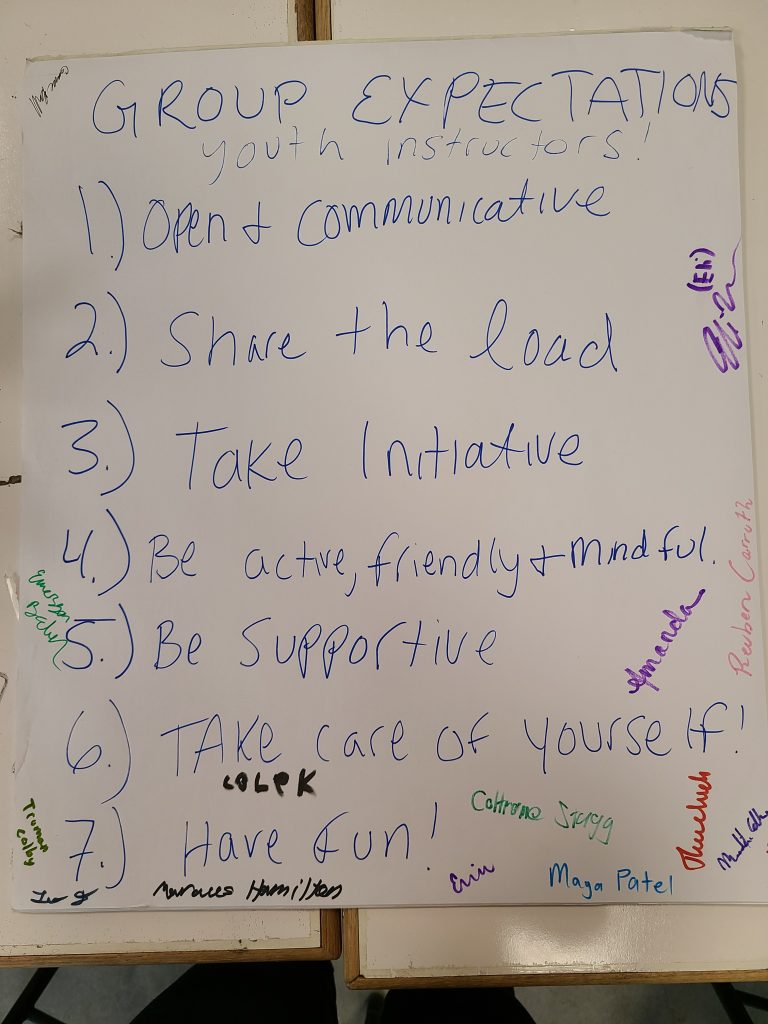

Erin said that she is often wary of introducing competitive challenges that might cause hurt feelings among students. So, the students created a “community contract,” in which they agreed to use kind words and be respectful of each other.

She also worked with her students to frame the competition not as the end goal but as an opportunity to test and iterate. After each competition, students asked questions such as, “What went well for their bots?” and “What didn’t?” before making adjustments. “Competing again and again became a way not to beat another person, but to continue to iterate and improve their design,” Erin said.

Giving Kids Space to Experiment

Emily Stanislawski, also a program instructor at WMSI, saw a lot of invention and experimentation among the group of eight elementary school-aged students who participated in her week-long game design camp.

The goal for the week was to create a playable game. On the first day of camp, Emily gave the kids “one-pagers” to help jumpstart ideas. These short guides provided students with sample code, images, and examples of types of games they could create.

Right away, the kids started experimenting with their own game concepts. One student picked up a storytelling one-pager that Emily had accidentally included in the pile and exclaimed, “oh, stories!” He then made up a character and a plot—“It was a knight going off to fight different monsters, until he had to face the final boss, which was a giant watermelon,” said Emily, who loves to see this type of inventiveness in her students.

Students tested each other’s games and shared feedback. “We emphasized that feedback helps you get better and helps things happen,” she said. “We wanted to stress the iterating part of the engineering design process,” she added.

This cycle of testing and tweaking your design to make it better can be frustrating for some students, but it is also where Emily sees students have “light bulb” moments when they discover solutions for themselves. She recalled seeing a student discover he was missing a ‘forever loop’ around an ‘if/then statement’ after she suggested he review his code step by step.

My goal as an educator is to guide them to figure things out on their own. My job isn’t to tell them things but to ask questions and reflect with them so they identify the issue and what might be a solution.

Emily Stanislawski, Program Instructor at WMSI

Tips for Creating Successful Playful Learning Experiences in Informal Learning Programs

Set open-ended objectives

For example, asking students to design a robot that can navigate a maze gives students direction but still allows for a lot of creativity in how they do it. Having each student or group come up with a different solution to the same problem is a powerful learning moment where groups can compare and contrast their ideas. For students who want a little more guidance, provide written and illustrated examples and prompts.

Be prepared to change tack

Be open to changing your lesson plan if student engagement is pulling the group in a different direction. Ask, “Will they still be practicing the skills I want them to learn?” If the answer is yes, let them continue; if it is no, nudge them toward a project aligned with their interests and with learning those skills.

Help students break down big ideas into small steps

Build in small, achievable milestones to help students who aren’t sure how to get started or who feel overwhelmed by a big project.

Create a culture where “failure” is celebrated as a learning opportunity

One way to do this is to avoid stepping in too soon when you see students not “getting it right.” Often, giving kids the time to work through a challenge can lead them to new discoveries. But do step in if student frustrations are preventing them from sticking with a project.

Cultivate observational skills in students

When students observe changes in their project they begin to ask “why?” Model these observational skills by stating out loud what you notice about their projects and the choices they’ve made. You can also ask students to explain their logic behind these choices and ask them to predict what they will do to their project.

Set boundaries but avoid long, instructor-led introductions

To allow their ideas to flow, give students the time and creative space to explore new tools at the start of a lesson or project. However, a space that is playful has structures to keep students safe and focused. Set boundaries about how and when tools can be used, for example.