Playful Learning Across Cultures

The classroom in Grovetown, New Hampshire, just south of the Canadian border, was buzzing with the “positive noise” Erin Glocke likes to hear. She’d given the group of elementary school students an engineering challenge: build a contraption out of LEGO pieces to safely deliver a LEGO figure down the paracord she strung from a doorknob to a table leg. Glocke is a program instructor for White Mountain Science, Inc. (or WMSI—pronounced “whimsy”), which offers playful year-round programming for grades K-12 in-school, after school, and through its summer camps. Sometimes Glocke has as many as 33 kids in her afterschool classroom. “There’s always lots of conversations and constant moving,” as students travel from their work-tables to the zip line to test their creations, she said. “It’s the right kind of noise when they’re talking about what they’re working on and sharing ideas.”

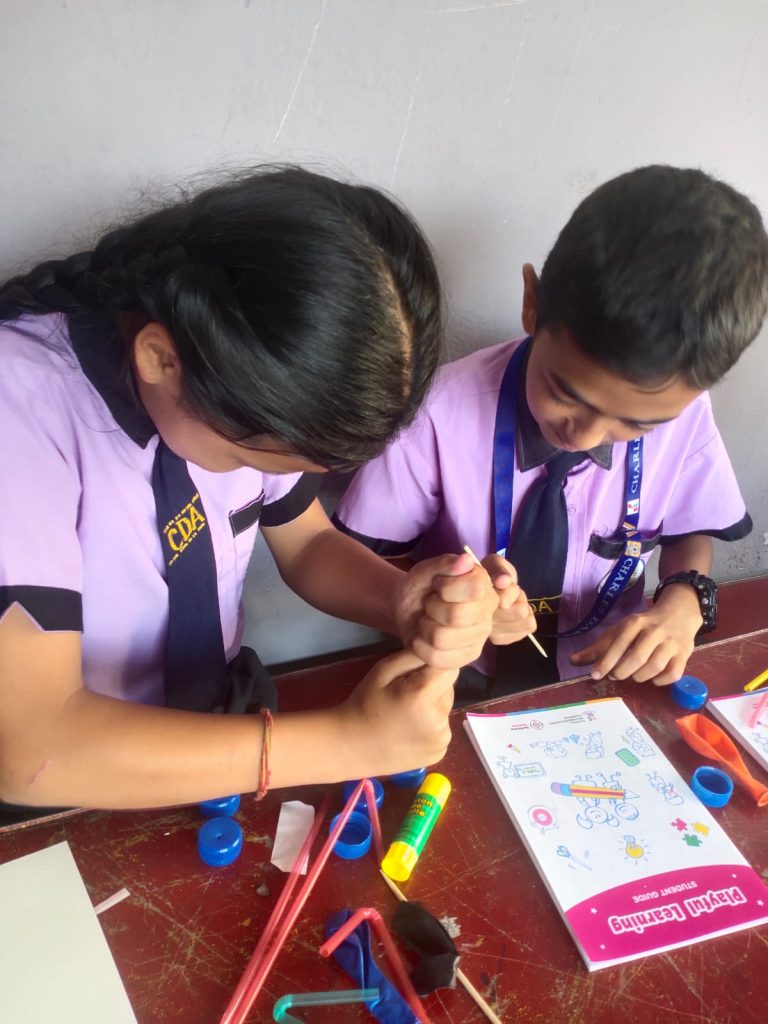

More than 7,000 miles away, about 35 kilometers outside of Kathmandu, Nepal, Dipen Pokhrel’s students regularly gather in the school’s makerspace to work on projects they will exhibit at one of the maker fairs students participate in several times a year. Pokhrel works for Teach for Nepal, which recruits and trains new university graduates to work in public schools in the Dang and Parsa districts. In the lead up to the fair, students visit the makerspace on Saturdays and Sundays, said Pokhrel. “We even give them the keys to the lab, so they can come any time,” he added.

Glocke and Pokhrel are among educators that are bringing playful engineering-based learning (PEBL) to classrooms across the globe in collaboration with Tufts University’s Center for Engineering Education and Outreach (CEEO) to get kids excited about and engaged in STEM. “Play is such an inherent way of learning. When you are enjoying something, and you’re actively engaged and curious about it, that’s where some of the deepest learning happens,” says Glocke.

Research published by the LEGO Foundation shows that learning that brings forth the characteristics kids exhibit when they are “at play”—such as feeling engaged, being self-directed, having fun, and finding the experience meaningful—enables students to develop a deeper understanding of content and a greater ability to apply new skills to different situations.

“We’ve seen across all the PEBL sites we work with that when students are given materials and challenges that allow them to try their ideas and to explore concepts in engineering and science — they dive in and do amazing, creative things. Moreover, besides learning content they also learn that they can be creative changemakers in the world,” said Merredith Portsmore, director, Tufts CEEO.

Among the projects Pokhrel’s students built was a model of a drip irrigation system to combat drought and a solar-powered house to solve the blackouts that are typical in this rural area of Nepal. Another student took home tools to build a chili-pepper-cutting machine to help his mother in the kitchen, said Pokhrel.

Building knowledge through play

At first glance, it might be hard to understand what’s happening when students are engaged in playful learning. But “they’re never ‘just playing,’” said Tom Tomas, of his students at Little Singer Elementary School in Birdspring, Arizona. Recently, Tomas challenged his 6th grade class to use LEGO SPIKE Prime kits to build a robotic rover inspired by the one Artemis astronauts will use to navigate the moon’s surface. “They’re learning about the moon as a natural system. They’re learning about engineering. They’re making meaning about what astronauts, engineers, and scientists do to prepare for the Artemis trips to the moon,” he said.

They’re never ‘just playing.’

Tom Tomas, 6th grade teacher, Navajo Nation

Tomas’s students sit in groups of twos or threes; some of them write and test word block code while others are tinkering and rebuilding their robots. There is a lot of talking and sharing of ideas, he said of the atmosphere of his classroom. “If there’s no collaboration; it isn’t engineering,” he added.

The iterative nature of play helps build knowledge, said Emily Stanislawski, who also teaches at WMSI. As a kickoff to more in-depth physics and geometry content, she asked her high school sophomore students to build catapults using popsicle sticks and a plastic spoon. Then she challenged them to see who could launch pom-pom balls the furthest. Students got busy building, testing, and adjusting their catapults until they found the launch angle that maximized the travel distance of their projectiles. By trying things over again and again, students tested their ideas and built on what they’ve learned, she said. Through their natural inclination to iterate while “at play,” her “students got a really, really tangible idea of how motion works,” she added.

Developing Social-Emotional Skills

Beyond strengthening their understanding of content, play-based learning gives children opportunities to practice a broad spectrum of social-emotional skills. Pokhrel has seen his students develop their abilities to work with others, regulate emotions, and communicate ideas. When he first brought PEBL activities to his students, they’d jump into their engineering challenges without talking to their team members. But over time, and through many team-building activities, they’ve learned to listen, observe, and brainstorm. “They’ve become much more emotionally aware,” he said. They’ve also become more conscientious and interested in other students’ perspectives, regardless of how familiar those students are with the content. For example, he said, students who had more experience with STEM competitions “actually sat back and let others in the group step up because they’ve learned that everyone can be great at finding solutions.”

They’ve become much more emotionally aware.

Dipen Pokhrel, educator, Kathmandu, Nepal

Samuel Havugimana, a science teacher at a public secondary school in the Bugesera District of Rwanda, appreciates the opportunities for interdisciplinary instruction that playful learning offers. He brought a “novel engineering” activity to his high school-aged students. In novel engineering, students use stories as the basis for engineering design challenges. He asked his students to identify problems the story’s characters were having and then brainstorm solutions. Havugimana said the activity helped his students see themselves as problem solvers in a way that rote chemistry lessons couldn’t, he said. “When they made soap, the only question to answer was, ‘did it work?’” he said. But with the more playful, novel engineering activity, “they need to analyze; they need to think about, ‘how do you design this?’” They begin to recognize that everyone in the group has valuable ideas, said Havugimana, who hopes that when students graduate and go back to their communities, “they can say, ‘I’m a problem solver.’”

They can say, ‘I’m a problem solver.’

Samuel Havugimana, science teacher, Bugesera District, Rwanda

Teaching Challenges

While the benefits are apparent, play-based learning is not always easy to implement. “Teachers and schools everywhere are required by the systems they exist in to tell students as much knowledge as possible. Hence, it is a challenge to fit these PEBL projects into their day,” said Portsmore.

Glocke suggests teachers look for moments during a lesson to allow for “solution diversity,” such as by providing students with a range of materials or options for what their final products can look like. “The more opportunities students have to play around with their own imaginations and interests, the better,” she said.

Just like we tell kids that they need to iterate;

Emily Stanislawski, program instructor, Northern New Hampshire

we also need to iterate the way we teach.

Stanislawski advises teachers not to be disheartened if their attempts to bring playful learning to their classrooms don’t work the first time. “It’s going to take practice, like any skill. Just like we tell kids that they need to iterate; we also need to iterate the way we teach.”

Pradeep Shrestha, a science teacher in rural Nepal, found he needed to change his approach with students because “free, unstructured play simply didn’t work; they didn’t know what to do with the materials I gave them,” he said of the hands-on, interactive STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) kits and curricula provided by Karkhana Samuha, a Nepali non-profit aimed at bringing innovation in education to marginalized communities. When he joined the under-resourced community school, his students had been without a science teacher for more than a year, and many of them lacked a foundational knowledge of the STEM concepts he and his colleagues were expected to build upon. In addition, many students miss school during harvest season to help their families work on their farms.

Shrestha showed the students how to build a balloon-powered car step-by-step by attaching four bottle caps to a piece of cardboard and fastening a filled balloon to the back. Then he asked his students analytical questions like, “Why did the car move in a forward direction?” and “Why did some groups’ cars move further than others?” The guided lesson was much more successful than unstructured play in helping students experience and establish their own theory of Newton’s third law of motion, he said, because they didn’t get frustrated and give up.

Honoring students’ culture and language

Encouraging students to express themselves and their identities is one way to engage students, say researchers. Rupa Manadhar, a principal and science teacher in Kathmandu, Nepal, saw success when she led an activity on cinematic storytelling. Her students come from a range of ethnic backgrounds, so she asked them to tell the stories of their cultures’ carnivals with their films. “One of my most restless students made the best story,” she said.

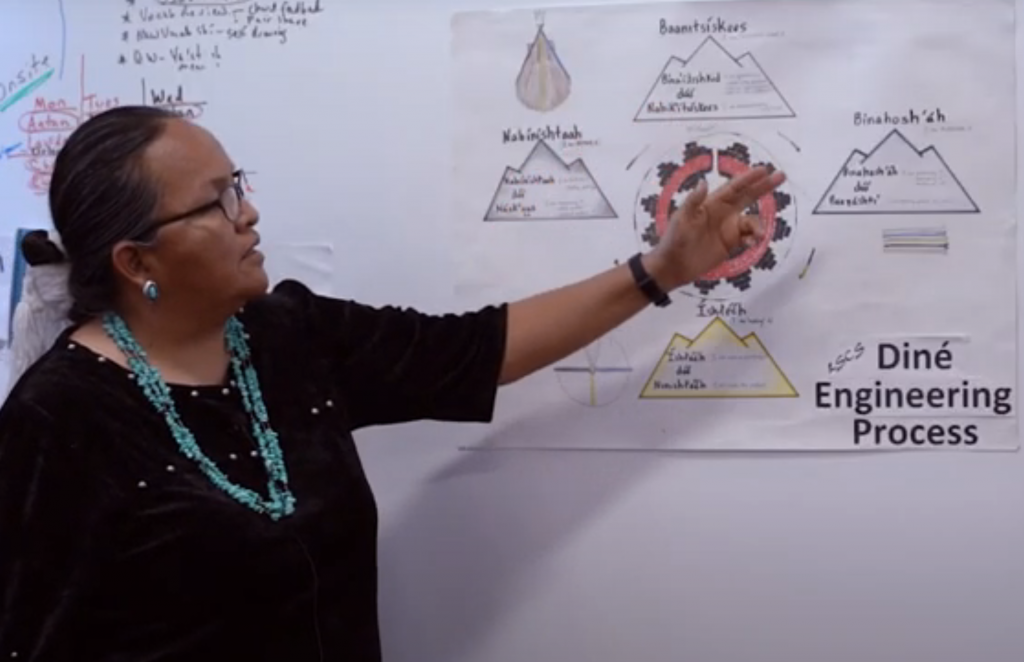

Honoring students’ culture, language, and heritage elevates students’ sense of worth, said educators at Little Singer. This is one reason Wilphina Becenti, who teaches language and culture at the school, embeds Diné (or Navajo) culture, teachings, and language into everything she does at Little Singer.

Diné live in kinship with our natural surroundings, said Becenti, who saw the Artemis project as an opportunity to help students develop a deeper connection with their homeland and heritage and validate the traditional and cultural knowledge passed down for generations. Becenti taught students the Diné words for hill and crater as they studied the lunar surface. They also researched the land where their families lived for generations, in part by interviewing parents and grandparents.

Before the Artemis project, “90% of them didn’t know their homeland or why that was important to who they are,” but now they do, she said. Shortly after her students completed the Artemis project, Becenti overheard one of her students introduce herself to elders in the Diné tradition, which includes describing the land of one’s ancestors. “The elders immediately understood… what line she’s from,” said Becenti. “That connection right there, that’s important.”