Instructional Technology for Student Engagement in Learning Anatomy

Dr. Jeffrey Marchant, Research Assistant Professor of Integrative Physiology & Pathobiology at TUSM, joined the 2016-2017 Instructional Technology Exploration Program (ITEP), offered by Tufts’ Educational Technology Services, with the goal of improving learning through interactivity. Here are his reflections on the project:

Why did you want to try a new approach in this particular class?

In the Head and Neck portion of the anatomy course the foundation for much of the content is the osteology. Many of the nerves, muscles and blood vessels have names based on the surrounding osteology so a thorough understanding of the bones makes learning the rest easier. In addition, the various fissures, canals and foramina provide an essential framework to ask clinical questions; for example, “If foramen ovale is damaged, what functions are compromised?”The answer will necessitate recall of somatic motor and sensory pathways as well as autonomic ones. This class is taught the first week of Head and Neck Anatomy, and I wanted to send the signal to students early on that material can be learned in class. I hoped this “jump start” on learning the material would make learning the rest that much easier. Ideally, the students would transfer this skill to other topics and try to get the most out of any class time, regardless of format.

What do find appealing about interactive classes?

Lectures represent an excellent mechanism for delivering content to students but not a useful mechanism for students to learn content. I consider a good lecture to be much like a good documentary: a concise, informative and perhaps entertaining delivery of information. Should we ask students to come to class to watch a documentary when they could more easily do that on their own time? With the ever-increasing volume of material the students must learn, the best use of class, and faculty, time is to facilitate the learning process. By providing the students with a video (documentary) prior to class that delivers the content, we can use the class time to push students to use that new knowledge and thus help move it into their working memory. One of the unfortunate consequences of many lecture-based classes is that most of the student learning occurs after class, in the absence of faculty input.

Qualtrics is a versatile survey tool provided for free to Tufts faculty and students. Learn more . . .

You tried two new tools to make your classmore engaging: the Complete Anatomy app and Qualtrics. How did this approach work?

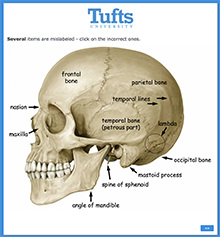

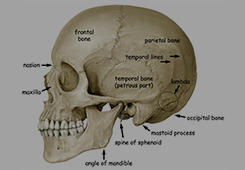

The Complete Anatomy app (3D4Medical) provides an excellent, realistic 3D experience viewing a skull. The images can be rotated, bones subtracted and soft tissues (arteries, nerves) added at will. This comes very close to having a small group session where a real skull is passed around and discussed. The Qualtrics online survey tool provides an excellent student engagement experience where answers to questions are scored on student devices and then collectively displayed on the screen. For example, in a “heat map” type of question, I might ask the students to view a labeled image and ask, “What has been mislabeled?” After discussing the question they can indicate their response(s) on their device and all responses can then be displayed on the main screen (as dots over their selected regions). Qualtrics offers 22 different types of question formats so the experience is much more varied than with simple multiple-choice questions (MCQs), and I’ve found this variety helps to maintain student interest. One has to be careful with question design, however, since not all answer displays on the main screen are useful. For example, a MCQ may use a histogram to display the answer spread, but interpreting these results in real time may be too time-consuming. Although I didn’t use them, Qualtrics permits the use of video clips and sounds in the stem, so the types of questions one can ask are really unlimited.

What are some lessons learned that you might share with others?

In interactive classes (or in lecture-based classes where I intersperse questions) I generally give students 1.5 to 2 minutes to work through a question. I’ve learned that this may not always be sufficient. Many of the questions in Qualtrics can be made complex and these take time to solve but the time is well spent: the process of solving the question and discussing the distractors is invaluable to learning. I’m often amused when I witness a lecturer ask a question in class and expect an immediate answer. This puts the students on the spot and it can become more of a negative experience than a positive one.

What are you interested in exploring next as part of your teaching?

Although I believe the experience of cadaveric dissection is essential to learning anatomy, the fact is that essentially all students will never see anatomy like this ever again in their careers. The type of anatomy they will nearly all see, in contrast, will be radiological images (CT, MR, plain films, etc). Ideally we should train the students to learn cadaveric and radiological anatomy at the same time. Although we currently do have radiology lectures, we can do a much better job of “cross-training” where both are more integrated. With the advent of the new anatomy lab and adjacent classroom, I’m hoping to work with radiologists to develop case studies that each table would work through as a group. The content would directly overlap the dissections being done and thus serve to both reinforce and expand the content. Ideally we would have set times for working through the cases (with each block serving one third of the class since this is the classroom capacity) and have radiology faculty present.