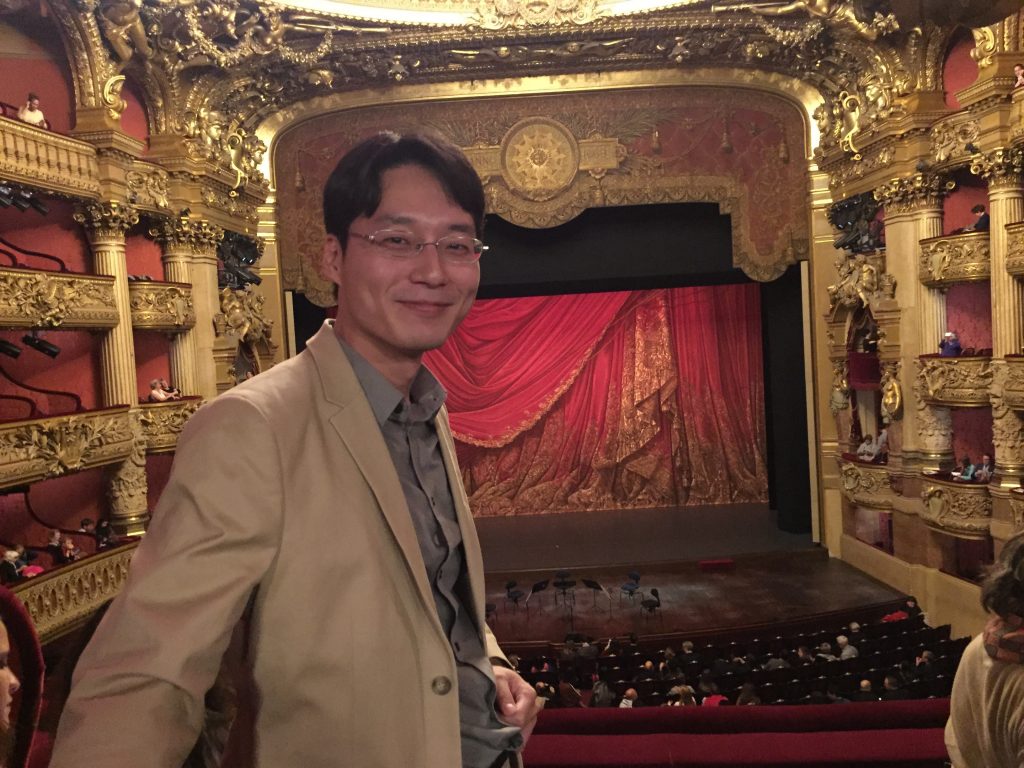

Tatsuo in Paris

Students have been sharing their stories on the blog for quite a while now, but this is the first year when one of the writers pursued an exchange semester. Ever-intrepid Tatsuo spent the fall at Sciences Po in Paris.

In the third semester of my MALD study, I decided to join an exchange program in Paris. I wanted to study international relations from another viewpoint, though I know that Fletcher and the hills of Medford/Somerville are the best place in the world to study.

I spent my semester at the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po. Sciences Po is one of the best schools for politics and international relations in Europe. It was founded in 1872 just after Franco-Prussian War. French elites were shocked by their country’s defeat and also impressed by the power of Prussia, and they faced the need to change their education system. Sciences Po was the result of the effort to improve French practical education, based on the philosophy of political realism. The symbol of the school, the fox and lion, originated from Machiavelli’s phrase “be smart as a fox and be strong as a lion,” and shows what the founders felt they needed.

I spent my semester at the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po. Sciences Po is one of the best schools for politics and international relations in Europe. It was founded in 1872 just after Franco-Prussian War. French elites were shocked by their country’s defeat and also impressed by the power of Prussia, and they faced the need to change their education system. Sciences Po was the result of the effort to improve French practical education, based on the philosophy of political realism. The symbol of the school, the fox and lion, originated from Machiavelli’s phrase “be smart as a fox and be strong as a lion,” and shows what the founders felt they needed.

At Sciences Po, I took five courses — Grand Strategy in Diplomacy, Past and Present; Building Long-Term Relationships and Sharing Value with Stakeholders; Political Speechwriting; African Key Economic Issues; and Economics and Globalization — to earn four Fletcher credits, and I audited two more courses, Japanese Politics and International Relations; and French A1 (elementary French).

All the courses I took, except French A1, were taught in English; thus, the basic materials and styles were not so different from what I encountered at Fletcher, but there were still some interesting differences between a French (or European) school and an American school.

For diplomatic issues, I took a grand strategy course, mainly focusing on security strategies, taught by the former minister of foreign affairs of Costa Rica. In the course, and in other discussions of diplomatic topics, people mainly followed realism — based on basic political realism theory and great figures like Machiavelli, Clausewitz, and Bismarck who I “met” in the U.S. However, the “realism” I studied in Paris was a little different from what I learned in the United States. In discussions I had at Fletcher and other places in the U.S., people argued the survival of the state must outweigh all other concerns. Thus, there were many options that could be taken, including unlawful or unethical means. Additionally, the strategies for security tend to justify unilateral actions. On the other hand, the discussions in Paris I faced tended to exclude such unlawful, unethical, or unilateral options, intentionally or unintentionally.

On development issues, French development studies consider the historic background of developing areas, while American studies mainly focus on the current situation. Sometimes, French professors’ attitudes looked more emotional than rational. On the other hand, these attitudes or analyses brought me a deeper understanding of the regions and the people to be developed. Additionally, these attitudes were understandable and maybe useful for me, a Japanese development officer, because we also have complex historical backgrounds with the Asian countries we once occupied.

One of the most interesting courses in Paris was Political Speechwriting. In the French school, theoretical studies seemed to be the majority, while American professional schools like case studies. Even in the practical course for speechwriting, the professor took a lot of time to introduce many theories of Greek and Roman rhetoric. When I took the course, it was the very interesting time after Brexit. In that context, the professor analyzed American presidential debates and shared his concerns about the French presidential election coming up next spring. Through the course, I realized the great advantage of theoretical studies. At that time, most American (and global) media criticized Trump’s speeches and judged Clinton to be the winner of the debates. On the other hand, the professor evaluated Trump’s speeches in terms of their technical rhetoric while many people, including me, tended to analyze the speeches based on their content. The result of the election proved the advantage of objective/unbiased analysis based on theoretical studies.

Generally, my semester was a great opportunity to learn a lot regarding the different perspectives of the U.S. and Europe. In Japan, we tend to think of “the West” as a single actor and a single set of values. In the U.S., we tend to think of the American standard as the global standard. The three months in Paris gave me the background knowledge to avoid such misunderstandings.

It was surely true that everything went well in Paris. But I missed the family atmosphere at Fletcher, including its flexible and warm administrative offices and the close connections between students and faculty. I also missed the great academic resources around Boston. And I also love the comfortable hilltop more than the crowded buildings filled by thousands of students in the small campus in the middle of Paris.

In the end, the three-month exchange program was both long enough and short enough for me, even if it was too short to learn French, to explore Paris and other areas of France and Europe, and to enjoy the great food and drink culture.