The next reading list — from Roxanne

With each of the utterly optional summer reading lists I’ve posted so far, another has emerged. Last week, Roxanne (who wrote for the blog from 2012-14, while she was in the MALD program, and is now a PhD candidate) asked me if I would like an additional list, this time focused on writers who are less often represented by traditional curricula. I was delighted to receive her offer and I’m even more delighted to share her suggestions with you. I’ll let Roxanne take it from here.

When we founded the Gender Analysis in International Studies Field of Study at Fletcher, a key tenet was that gender is not merely about identities or social relationships. Rather, it is also about institutions, notions of credibility and authority, and — at its heart — about power. Because gender does not exist in a vacuum, we considered how it intersects with race, social class, ethnicity, and other vectors, to affect conceptions and experiences of agency, vulnerability, power, or justice.

When we founded the Gender Analysis in International Studies Field of Study at Fletcher, a key tenet was that gender is not merely about identities or social relationships. Rather, it is also about institutions, notions of credibility and authority, and — at its heart — about power. Because gender does not exist in a vacuum, we considered how it intersects with race, social class, ethnicity, and other vectors, to affect conceptions and experiences of agency, vulnerability, power, or justice.

As we looked at syllabi, we asked ourselves: Who is considered an authority on international studies and why? Which texts count as “the canon” — and which voices and opinions are left out of that imagination? These are questions I have taken to asking about my leisure reading as well. How are my notions of what is worth reading colored by gendered, ethnicized, and racialized expectations surrounding credibility and authority? With that in mind, and with a commitment to interrupting the white-American-male streak on my own bookshelves, I am delighted to share a few of my favorite reads from the past year.

A common theme in the books I have read this year has been that of how people negotiate their relationship to solitude and their yearning for community. I discovered Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone on the end-of-year round-up of favorite books in the Brainpickings newsletter. Laing’s words at the conclusion of a tour through solitude, art, and urban alienation felt particularly timely: “Loneliness is personal, and it is also political. Loneliness is a collective; it is a city. As to how to inhabit it, there are no rules and nor is there any need to feel shame, only to remember that the pursuit of individual happiness does not trump or excuse our obligations to each another.”

Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing tackles the ways in which legacies of power, oppression, and loss layer atop each other from generation to generation. It is the kind of book that lodges itself in your mind, and it reminded me of a mix between Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s magical realism and Hanya Yanagihara’s punching descriptions of life-long hardship.

Part of my professional work in the past year has centered on understanding the journeys of refugees, through a study I have co-managed with Professor Kim Wilson in Greece, Jordan, Turkey, and Denmark. During the research methods summer seminar I participated in last year, one instructor had pointed out that academic writing is anemic when it only draws on scholarly texts. A number of literary works on the experience of displacement have since been piled on my desk alongside our own footnotes.

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s short story collection The Refugees stirred me on many snowy February nights and Roberto Bolaño’s words in its epigraph still travel with me: “I wrote this book for the ghosts, who, because they’re outside of time, are the only ones with time.” Valeria Luiselli’s Tell Me How It Ends, a long-form essay on immigration to the United States, also rang close to home. Luiselli weaves her own insights as a new immigrant — a “resident alien,” in the words of Luiselli, the law, and my own experience — with her observations of the experience of Central American children seeking to avoid deportation from the United States. Luiselli’s articulation of “the great theater of belonging” that immigration and nationhood invite and require has accompanied me as we work on the final report of our own refugee study.

One of the losses of displacement (even chosen displacement) is the ease of one’s own language. I was born and raised in Greece, but, by virtue of where I live and my current research on Colombia, my life now unfolds primarily in English and in Spanish. Until recently, I used to interact with Greek predominantly in the context of bureaucracy. When my friend Niki introduced me to Titos Patrikios’ The Temptation of Nostalgia, the title felt like a phrase in which I have lived. The book itself did not disappoint, and it prompted a return to Greek literature and a reacquaintance with the Greek language of joy, dreaming, and lightness.

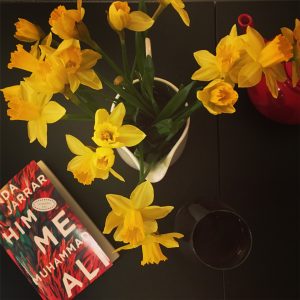

I am new to short stories and have discovered two of my favorite collections in the past year. Kathleen Collins’ Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? came into my life through an excerpt in literary magazine Granta’s “Legacies of Love” issue. Collins writes injustice and structural violence with such subtlety that a sense of activating grief lingered long after I finished the book. My other favorite short story collection was Randa Jarrar’s Him, Me, Muhammad Ali. Jarrar writes about foreignness, youth, queerness, desire, and loss with a lightness that leaves her readers dizzy and that has me wanting to read much more of her work.

I am new to short stories and have discovered two of my favorite collections in the past year. Kathleen Collins’ Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? came into my life through an excerpt in literary magazine Granta’s “Legacies of Love” issue. Collins writes injustice and structural violence with such subtlety that a sense of activating grief lingered long after I finished the book. My other favorite short story collection was Randa Jarrar’s Him, Me, Muhammad Ali. Jarrar writes about foreignness, youth, queerness, desire, and loss with a lightness that leaves her readers dizzy and that has me wanting to read much more of her work.

Finally, what is on my summer to-read list? Besides a lot of research-oriented reading on the Colombian peace process in preparation for my upcoming fieldwork, I am looking forward to Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (furthering the refugee theme), Hisham Matar’s The Return (a memoir of, among other issues, fatherlessness), and Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay With Me, a novel tracing a Nigerian couple’s parallel accounts of a marriage. Happy reading!